It appears to be a most peculiarly British spectacle; the Home Secretary, herself a creature most strange to the aromatic smoke of the protestor’s fire, has declared in tones of the utmost gravity that any soul daring enough to deface that solemn war memorial, the Cenotaph, should be dispatched post-haste to the clink, and with such velocity that their feet would scarcely graze the earth. Suella Braverman, who made this remark, is reported to have never frolicked in the fields of protest herself, lending a certain air of the theoretical to her spirited defences.

The lady did aver, with all the force her office commands, that she would leap into action, should the constabulary require yet more potent weapons in their arsenal to combat demonstrations turned distasteful. The whiff of burning effigies and the sound of the chant and jeer have transformed, in her eyes, from the healthy exhalations of a free society to the miasma of ‘hate marches.’

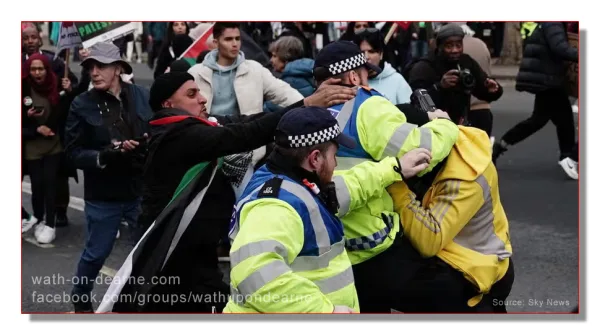

As throngs took to the London streets, they may well have pondered the old puzzle: when does the right to speak pugnaciously of injustice bleed into the sin of hatefulness? The Cenotaph stands, after all, not just as stone and inscription but as a sentinel to liberty hard-won.

Amid the impassioned cries for ceasefire in lands far from the relative peace of Whitehall, one is reminded of the perpetual rhythm of history: the protest, the crackdown, the incensed outcry from officials who never themselves smelt the fumes of public dissent.

One understands, with a weary resignation, the Home Secretary’s admonition that any assault on the solemnity of Armistice Day shall be met with the full severity of the law. Yet one cannot help but ponder the irony: that in remembering the fallen who died for freedom, one must curtail the very freedoms they died to protect.

The Cenotaph, an altar to the Unknown Warrior, could become the axis upon which the great wheel of debate turns, as the country navigates the uneasy truce between order and liberty. And in the end, what remains is the indelible image of protest – a tableau as British as the rain-soaked streets of November and as timeless as the struggle for peace itself.

Leave a Comment